Kidneys play a vital role in keeping the body healthy by filtering blood and removing excess fluids through urine. They also help maintain the balance of important substances like salt, potassium, and acid levels. When kidneys are not functioning properly, dialysis can step in to do some of these tasks. Chronic kidney failure (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are common conditions that may require dialysis. If left untreated, these diseases can lead to serious health complications and even death. While dialysis is an effective treatment option, it is not a cure for kidney disease or failure. There are two types of dialysis: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

As part of the clinical training in Semester 4 of the nursing programme at IMU, each student has the opportunity to spend a day in the HD/CAPD unit at Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar, Seremban (HTJS).

At the Hemodialysis Unit

Hemodialysis (HD) is a treatment that uses a dialysis machine, and a filter called a dialyzer to clean blood and act as an artificial kidney. An arteriovenous fistula is created before starting hemodialysis to provide access to the blood vessels for the dialyzer.

Upon our arrival at the unit, it was evident to us that there is a high level of organisation in this unit. Dr Radha, our lecturer for renal, explained that this meticulous organisation was imperative because dialysis patients can deteriorate very quickly, and everything needs to be readily available for immediate intervention.

The unit is air-conditioned and divided into cubicles, each with a few hemodialysis machines next to comfortable armchairs. Small details, such as the plush armchairs, greatly enhance patient comfort, which is important as patients spend half their week in this environment. There is also a specialised cubicle for patients with infectious conditions, like Hepatitis B and C, to prevent cross-contamination of equipment between patients.

Reverse Osmosis Room in HD unit

Reverse Osmosis is the most dependable water filtration method used to prepare water for hemodialysis. Common components of dialysis water systems include a combination of pre-filter, also known as Sediment Filter, Carbon Filter, water softener, and Reverse Osmosis (RO) system which helps in removing potentially harmful water contaminants such as aluminum, chloramine, fluoride, copper, and zinc as well as bacteria and endotoxin.

Within the HD unit, it was placed in the back room where it is accessible to nurses and dialysis technicians.

Dialyzer-Cleaning Room

Right next to the reverse osmosis room lies the Dialyzer-Cleaning room where the dialyzers are placed and cleaned thoroughly. A dialyzer is often referred to as an “artificial kidney” made of thin, fibrous material where the function is to remove excess waste from the blood via ultrafiltration. On the left side of the room, there was a whole cupboard used to separate each patients’ dialyzer with their personal details and the date of when the dialyzer is first used. With the help of Dr Radha Maniam, we were able to differentiate the various types of dialyzers that are available for patients. On the other hand, a few machines that are responsible for cleaning dialyzers are placed on the right side of the room.

Our Experience

After spending some time at the HD unit, we were able to gain a more realistic understanding of a patient’s routine by combining our theoretical knowledge with what we observed firsthand. Everything was efficiently scheduled in the unit and patients arrived on time for their sessions, resulting in minimal delays.

Upon arrival, patients would check their pre-dialysis weight and receive assistance from nurses in inserting arterial and venous catheter into their fistula, which would then be connected to the dialysis machine. The filtering process would last for approximately four hours, during which time most patients could remain immobile and attached to the machine while working on other activities like chatting with family or friends, or even studying.

I was encouraged to see that most patients were able to carry on with their lives despite their dependence on the machine, thanks to the advancements in science and technology that created it. Once the machine signaled that the desired filtration had been achieved, the remaining blood would be pumped back into the patient’s body. The catheters would then be removed from the fistulas, and pressure would be applied for 5-10 minutes, followed by a compression bandage that would be left on for several hours to prevent bleeding. Patients would then check their post-dialysis weight to estimate how much fluid they could consume before their next session.

Throughout the day, we had the privilege of observing several nurses as they went about their work in renal nursing. We were impressed by their meticulous attention to maintaining sterility, a crucial aspect in preventing infection. The nurses were generous with their time, teaching us about their roles and demonstrating how they assembled and disassembled the equipment. We noticed that many patients and their family members were already familiar with the standard procedures for hemodialysis, having undergone the process for years. We took the opportunity to learn from them, engaging in conversations with various patients as we moved around the HD unit.

From these conversations, we had the opportunity to hear a diverse range of stories from many different patients from all walks of life, with the youngest patient we met being 9 years old and the oldest around 90 years old. Listening to their firsthand sharing gave us valuable insights into the life of a renal patient dependent on a machine for the rest of their life. Their input deepened our empathy for their condition, helping us identify areas where we can offer improved support throughout their lengthy journey. This experience was instrumental in shaping us into more compassionate and effective nurses.

Another observation we made during our observation throughout the day is that patients adhere to a consistent and unvarying schedule for their dialysis appointments, arriving at the same time each week and encountering the same individuals at those times. This regular and extended interaction in the unit has led to the formation of numerous friendships among the patients, with some even referring to each other as their “second family” due to the frequency of their encounters.

It warms our heart to see this little community that they have formed among themselves where they support each other from within, with patients helping each that other with their machine setup and checking in on each other’s family However, not all were coping well with a small number of patients having slight depressive tendencies and a negative outlook of life due to their dependency on this machine for life, as evidenced by verbal sayings like “What is the point, we are all just waiting to die” and “It’s better I die now than do this for the rest of my life.” Though depressing, these conversations really showed us what kind of support they need and how we can better validate and support these patients throughout this rough patch of life in their long journey of dialysis.

Continuous Ambulatory Peritoneal Dialysis (CAPD) Unit

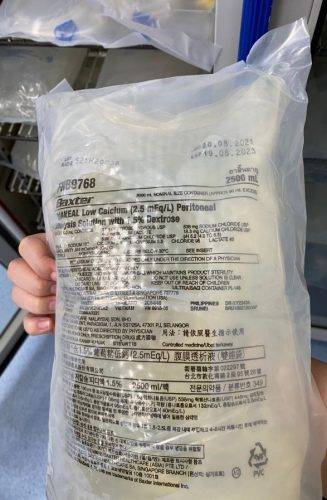

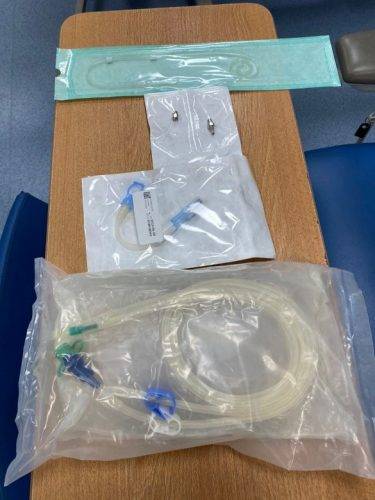

In contrast to the former, peritoneal dialysis (PD) is performed at the inner lining of your abdomen which acts as a natural filter. Dialysate, a purifying liquid that cycles in and out of the abdomen cavity, with the help of a Tenckhoff catheter that is placed in the abdomen by surgery. Furthermore, there are two types of peritoneal dialysis which are continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and automated peritoneal dialysis (APD). Both serve the same basic treatment but the number and the method of treatments are different, which may be convenient for different types of patients.

Unfortunately, there were no patients who booked an appointment for peritoneal dialysis on the day we visited the HD/CAPD unit.

However, huge thanks to Dr Radha Maniam for teaching us about the different types of dialysis solutions used for peritoneal dialysis. The fluids were placed in a specialised fridge to preserve the solution, whereas items such as tenckhoff catheter, disposable tubing, and drain bags were placed in another room accessible only to healthcare professionals.

Conclusion

After spending a day at the HD/CAPD unit, we gained many valuable insights through observations of the nurses, discussions with our lecturer Dr Radha, and conversations with the patients. This experience has further enlightened us on the responsibilities and methods of assisting and supporting the patients throughout their dialysis sessions and their dialysis journey in the long run. We also had the opportunity to see and touch the dialysis machines and the other tools and equipment working behind the scenes to make everything run smoothly, like those at the dialyzer-cleaning rooms and water-processing reverse osmosis rooms.

It was also a humbling experience for us to converse with a diversity of patients who were literally walking encyclopedias of dialysis-related knowledge and listening to their emotional journey. We’re very grateful for this learning opportunity and found this field visit to be a very interesting experience and specialty field, and we are both excited thinking about the possibility of venturing further into this field. Ultimately, this has been a very unforgettable visit which we hope will shape us into better nurses as we integrate all that we have learned into our clinical practice in the near future.

Written by

Odelia Lee Yun Sze

Sidney Yong Mei Ling

Student Nurses, Cohort NU1/21

Reviewed by

Dr Radha Maniam, Lecturer

Odelia Lee Yun Sze and Sidney Yong Mei Ling (in the photo above) shares their experience at a HD/CAPD unit of Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar.

Odelia Lee Yun Sze and Sidney Yong Mei Ling (in the photo above) shares their experience at a HD/CAPD unit of Hospital Tuanku Ja’afar.