Second year International Medical University (IMU) medical student, Owen Tan, had the opportunity to do his three week medical elective in Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong for three weeks. Here, he relates his experience in Hong Kong.

In the universe, there are things that are known, and things that are unkown, and in between, there are doors. – William Blake

“Just leave it in the bag, we don’t need stethoscope. We are neurosurgeons, not neurologists.” The chief told me on my first day here. After my Semester 3 posting, I had the privilege to spend three weeks at Department of Neurosurgery, Queen Mary Hospital under the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong. I was attracted to their emphasis on bridging the gap between the clinic and laboratory, and integrating patient care with research interests. I made the initial contact with the Chief of Neurosurgery Department, Dr Lui who was very encouraging and I was able to secure a placement there.

On my first few days in Hong Kong, I was surprised to see the occasional citizen wearing a surgical mask on the MTR or a crowded city bus. Similarly, when I arrived at QMH, I was impressed with the institution’s strict infection control practices (the most visible symbols of which are surgical masks and frequent hand washing). I found the infection control video modules for medical students to be both detailed and highly informative. I later recognised that many of the systems currently in place at QMH to prevent the spread of infection were implemented in response to lessons learned from the SARS outbreak in 2003. According to WHO, over 1750 cases of SARS were identified in Hong Kong between November 2002 and July 2003, second to only the 5300+ cases documented in mainland China. Nearly 300 individuals with SARS died in Hong Kong, equivalent to a fatality rate of nearly 17%. Each day in the department started at 7am, where I followed the medical officers to assess the patients for overnight changes and write in their progress notes. Morning department meeting in conference room started promptly at 8am, where each patient would be discussed by their named physician or the assigned student doctor with the chief, assistant consultants, case manager (only in HK), senior resident, named nurse and social worker. Plans would be made for the day and it was then followed by grand ward round at 9:30am with the attending physician (consultant equivalent).

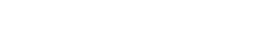

On my first few days in Hong Kong, I was surprised to see the occasional citizen wearing a surgical mask on the MTR or a crowded city bus. Similarly, when I arrived at QMH, I was impressed with the institution’s strict infection control practices (the most visible symbols of which are surgical masks and frequent hand washing). I found the infection control video modules for medical students to be both detailed and highly informative. I later recognised that many of the systems currently in place at QMH to prevent the spread of infection were implemented in response to lessons learned from the SARS outbreak in 2003. According to WHO, over 1750 cases of SARS were identified in Hong Kong between November 2002 and July 2003, second to only the 5300+ cases documented in mainland China. Nearly 300 individuals with SARS died in Hong Kong, equivalent to a fatality rate of nearly 17%. Each day in the department started at 7am, where I followed the medical officers to assess the patients for overnight changes and write in their progress notes. Morning department meeting in conference room started promptly at 8am, where each patient would be discussed by their named physician or the assigned student doctor with the chief, assistant consultants, case manager (only in HK), senior resident, named nurse and social worker. Plans would be made for the day and it was then followed by grand ward round at 9:30am with the attending physician (consultant equivalent).  They had their own neurosurgery intensive care unit which was just next to the ward. Most of the cases were referred from Accident & Emergency Department, ranging from those that had been taking in by the ambulance to those that had simply turned up to the hospital by themselves. Indeed, the healthcare system in Hong Kong did not include a general practice sector in the same way as the UK – therefore, anyone with any medical concern can present themselves to the hospital, unfiltered by GPs, and demand to be seen. All consultations with patients and ward round discussions were held in Cantonese, but the doctors spoke English too and were all incredibly approachable and keen to teach. On every Monday and Thursday afternoon, I would be at the neurosurgery outpatient department. At QMH, clinic rooms only had three walls. Instead of a back wall, a corridor at the rear connected around ten adjoining clinic rooms, so nurses could move swiftly from one to another. In addition to ward work, I was fortunate enough to join the lectures with medical students at Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, neuroimaging tutorials, final year medical student bedside teaching, and a neurological society meeting at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

They had their own neurosurgery intensive care unit which was just next to the ward. Most of the cases were referred from Accident & Emergency Department, ranging from those that had been taking in by the ambulance to those that had simply turned up to the hospital by themselves. Indeed, the healthcare system in Hong Kong did not include a general practice sector in the same way as the UK – therefore, anyone with any medical concern can present themselves to the hospital, unfiltered by GPs, and demand to be seen. All consultations with patients and ward round discussions were held in Cantonese, but the doctors spoke English too and were all incredibly approachable and keen to teach. On every Monday and Thursday afternoon, I would be at the neurosurgery outpatient department. At QMH, clinic rooms only had three walls. Instead of a back wall, a corridor at the rear connected around ten adjoining clinic rooms, so nurses could move swiftly from one to another. In addition to ward work, I was fortunate enough to join the lectures with medical students at Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, neuroimaging tutorials, final year medical student bedside teaching, and a neurological society meeting at Queen Elizabeth Hospital.  Usually after lunch, I would be in the Operating Theatres (OTs), which was directly opposite of out wards. They basically had scheduled “elective” surgeries every day in addition to the emergency surgeries. The OT culture involved going into the OT prior to the arrival of the patient, boldly initiating one’s introduction to the circulator and scrub nurses, saying hello to the anesthesiologist, getting oneself the appropriate gown and gloves, and then performing the necessary prepping (catheterising, shaving and etc). Scrubbing in was mandatory and done without question. It also meant that one stayed in the OT from beginning to end for all cases of the team, answering all relevant questions about the patients’ histories and anatomy. Writing up the post-operative notes with co-consult anesthesia was also to be done after accompanying the patient to the recovery room for hand-over. Due to the diverse patient population that the hospital served, I was fortunate to see a wide spectrum of surgery procedures for different conditions from embolization of arteriovenous malformation and carotid-carnernous fistula to EC-IC bypass using radial artery graft.

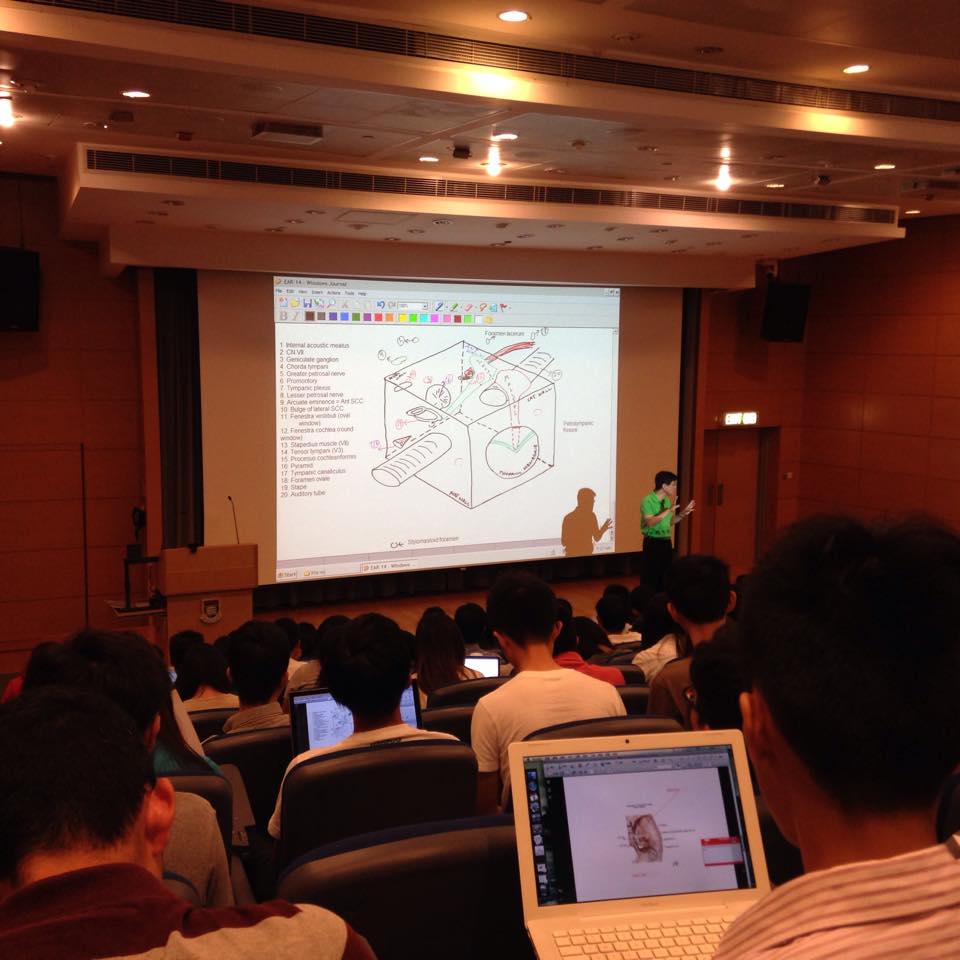

Usually after lunch, I would be in the Operating Theatres (OTs), which was directly opposite of out wards. They basically had scheduled “elective” surgeries every day in addition to the emergency surgeries. The OT culture involved going into the OT prior to the arrival of the patient, boldly initiating one’s introduction to the circulator and scrub nurses, saying hello to the anesthesiologist, getting oneself the appropriate gown and gloves, and then performing the necessary prepping (catheterising, shaving and etc). Scrubbing in was mandatory and done without question. It also meant that one stayed in the OT from beginning to end for all cases of the team, answering all relevant questions about the patients’ histories and anatomy. Writing up the post-operative notes with co-consult anesthesia was also to be done after accompanying the patient to the recovery room for hand-over. Due to the diverse patient population that the hospital served, I was fortunate to see a wide spectrum of surgery procedures for different conditions from embolization of arteriovenous malformation and carotid-carnernous fistula to EC-IC bypass using radial artery graft.  Hours of advance preparation of living life alone at Hong Kong could have never prepared me for the godsend of people I met there. Dr Lui, my supervisor at QMH, left a deep impression on me – a jolly mentor who loved to teach, he was always smiling, showered genuine care for his patients and team members alike, and took pride in his chosen profession. He took a keen interest in my progress and understood the difficulties I faced in coming from an entirely different environment. I still remembered his parting words fondly: “The patients don’t choose to be sick, but you choose to become a doctor.” The second person whom I met in the hospital was Dr Ivan, a visiting neurosurgery fellow from Switzerland at the same department, without whom my elective would have been very different (and much more alone). He helped me to familiarise myself with all aspects of hospital works, especially introducing me the neurosurgery terms such as AVM, ETV, moya-moya disease and so on. Dr Andrew was another. A houseman who worked for some time in UK, he was an important aspect of my life there – he gave me the chance to do some procedures in the wards and brought me for lunch most of the times. Living in the university hall with like-minded people, I also had the opportunity to work and learn alongside both medical and nursing students from all over the world. Educated through different healthcare system and having gone through various volunteering experiences, our individual passion for humanitarian served as a common denominator, creating the perfect environment for ideas to propagate.

Hours of advance preparation of living life alone at Hong Kong could have never prepared me for the godsend of people I met there. Dr Lui, my supervisor at QMH, left a deep impression on me – a jolly mentor who loved to teach, he was always smiling, showered genuine care for his patients and team members alike, and took pride in his chosen profession. He took a keen interest in my progress and understood the difficulties I faced in coming from an entirely different environment. I still remembered his parting words fondly: “The patients don’t choose to be sick, but you choose to become a doctor.” The second person whom I met in the hospital was Dr Ivan, a visiting neurosurgery fellow from Switzerland at the same department, without whom my elective would have been very different (and much more alone). He helped me to familiarise myself with all aspects of hospital works, especially introducing me the neurosurgery terms such as AVM, ETV, moya-moya disease and so on. Dr Andrew was another. A houseman who worked for some time in UK, he was an important aspect of my life there – he gave me the chance to do some procedures in the wards and brought me for lunch most of the times. Living in the university hall with like-minded people, I also had the opportunity to work and learn alongside both medical and nursing students from all over the world. Educated through different healthcare system and having gone through various volunteering experiences, our individual passion for humanitarian served as a common denominator, creating the perfect environment for ideas to propagate.

At the end of the elective, I was sad to leave. The path to getting there was admittedly fraught with obstacles as I am one of the few international visiting students to have attempted a neurosurgery elective there, but this valuable elective will remain in my memory forever. It was a combination of the people whose lives I had the good fortune to briefly cross paths with, exploration of the principles of healthcare beyond the scope of Malaysia’s system, as well as the growth I experienced as both a future medical professional and as a person. It is my fervent hope that more can be done to pave the way for medical students in IMU to partake in such surgical electives in HKU, and for my juniors to go forth and learn the experience of a lifetime, with an open heart and mind.

Queen Mary Hospital (est. 1937) is a 1400-bed tertiary hospital and the principal facility of the Hong Kong West Cluster, with a catchment area population of over 500,000 people. Stands at 28-stories as the tallest hospital building in all of Asia, one can see both the harbor and Victoria Peak from the neurosurgery ward on the seventh floor. On a sunny day, sun glints off the peaceful waters, and it is rather calming watching ferries leisurely traversing the waters. This center has pioneered the extracranial-intracranial (EC-IC) bypass procedure in Hong Kong which is a major breakthrough for cerebral revascularization in the treatment of aneurysm not amendable to endovascular embolization or conventional clipping. Cerebral aneurysm is a potential health hazard that occurs in about 2 to 6% of the population in Hong Kong. Aneurysm rupture is a cause of intracranial bleeding that may lead to severe disability and the death rate is as high as 45%. The risk of rupture of an aneurysm is about 1.3% per year.

Queen Mary Hospital (est. 1937) is a 1400-bed tertiary hospital and the principal facility of the Hong Kong West Cluster, with a catchment area population of over 500,000 people. Stands at 28-stories as the tallest hospital building in all of Asia, one can see both the harbor and Victoria Peak from the neurosurgery ward on the seventh floor. On a sunny day, sun glints off the peaceful waters, and it is rather calming watching ferries leisurely traversing the waters. This center has pioneered the extracranial-intracranial (EC-IC) bypass procedure in Hong Kong which is a major breakthrough for cerebral revascularization in the treatment of aneurysm not amendable to endovascular embolization or conventional clipping. Cerebral aneurysm is a potential health hazard that occurs in about 2 to 6% of the population in Hong Kong. Aneurysm rupture is a cause of intracranial bleeding that may lead to severe disability and the death rate is as high as 45%. The risk of rupture of an aneurysm is about 1.3% per year.

Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail. – Ralph Waldo Emerson